The art of curing meat is as ancient as civilization itself, a preservation technique born out of necessity that has evolved into a culinary tradition. Yet, even the most experienced charcutiers occasionally encounter the frustrating problem of overly salty cured meats. What appears as a simple miscalculation of salt measurement actually reveals a fascinating biochemical drama—the delicate balance of osmotic pressure gone awry.

When we rub salt onto meat for curing, we're initiating a complex molecular ballet. The salt doesn't merely sit on the surface; it begins to alter the very fabric of the meat at a cellular level. This process, governed by the principles of osmosis, typically creates an environment where moisture is drawn out while flavors concentrate. The intended result is preserved meat with concentrated umami and perfect texture. However, when this equilibrium fails, we're left with leathery, unpalatably salty results that even thorough soaking can't fully rectify.

The science behind this culinary mishap lies in the disrupted osmotic gradient. In properly cured meat, salt penetrates gradually, allowing interior moisture to equalize with the increasingly saline exterior. Cells release just enough water to create equilibrium without becoming desiccated. But excessive salt creates too steep a concentration gradient. Like a sudden tidal wave overwhelming a beach, the intense salinity difference causes cellular water to rush out violently, leaving protein structures permanently damaged and salt crystals embedded where they don't belong.

Traditional curing methods developed safeguards against this imbalance. The use of salt boxes—wooden containers where meat was packed in alternating layers with salt—allowed for gradual moisture exchange. The wood absorbed excess brine while maintaining humidity, creating a microenvironment where osmosis could occur at a measured pace. Modern vacuum-sealed curing often lacks this buffer system, making precise salt measurement absolutely critical.

Temperature plays a surprisingly pivotal role in osmotic control. Colder environments slow molecular movement, giving meat cells time to adjust to changing salinity. Many traditional curing cellars maintained temperatures just above freezing for this reason. Warmer conditions accelerate salt penetration while simultaneously increasing moisture loss through evaporation—a double threat to osmotic balance. This explains why summer-cured hams often turn out drier and saltier than their winter counterparts, even with identical curing times.

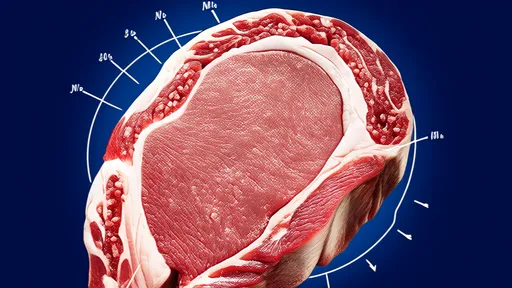

The meat's composition significantly influences osmotic outcomes. Well-marbled cuts with abundant intramuscular fat provide natural buffers against over-salting. Fat cells, being less permeable to water transfer, create microscopic compartments that maintain moisture even as surrounding muscle fibers lose water. This explains why fatty pork belly cures more forgivingly than lean game meats. The collagen matrix in connective tissue also resists complete dehydration, which is why cuts like pork shoulder withstand longer curing times.

Modern solutions to this ancient problem combine food science with tradition. Equilibrium curing—where meat and salt are precisely weighed to achieve perfect ratios—eliminates guesswork. Some contemporary charcutiers use salt brines with added phosphates, which help retain moisture by modifying protein structures. Others employ hybrid methods, starting with dry cures to develop flavor before switching to controlled humidity aging chambers. These approaches all aim to maintain that critical osmotic balance where moisture transfer occurs without cellular collapse.

The consequences of osmotic failure extend beyond taste. From a food safety perspective, properly balanced curing creates an environment hostile to pathogens while preserving meat texture. When osmosis is disrupted, surface dehydration can create pockets where moisture and bacteria become trapped beneath a hardened exterior. This explains why over-salted cured meats sometimes develop spoilage issues despite the preservative effects of salt.

Understanding these principles transforms how we approach meat preservation. What our ancestors learned through trial and error—the importance of environmental conditions, meat selection, and patience—now makes scientific sense. The difference between succulent prosciutto and inedible jerky often comes down to whether osmotic pressure worked with or against the curing process. In the delicate dance between salt and flesh, equilibrium isn't just desirable—it's everything.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025